We’ve got a problem

It’s systemic, and it’s killing us

Like the headline says, we’ve got a problem, and the problem is this:

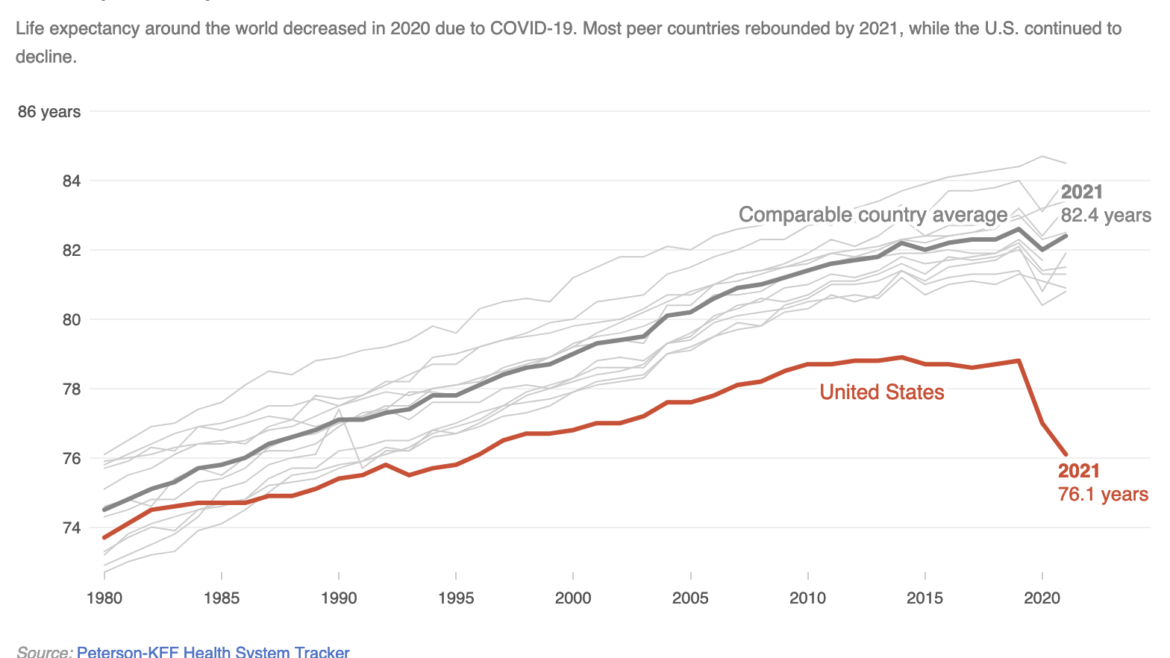

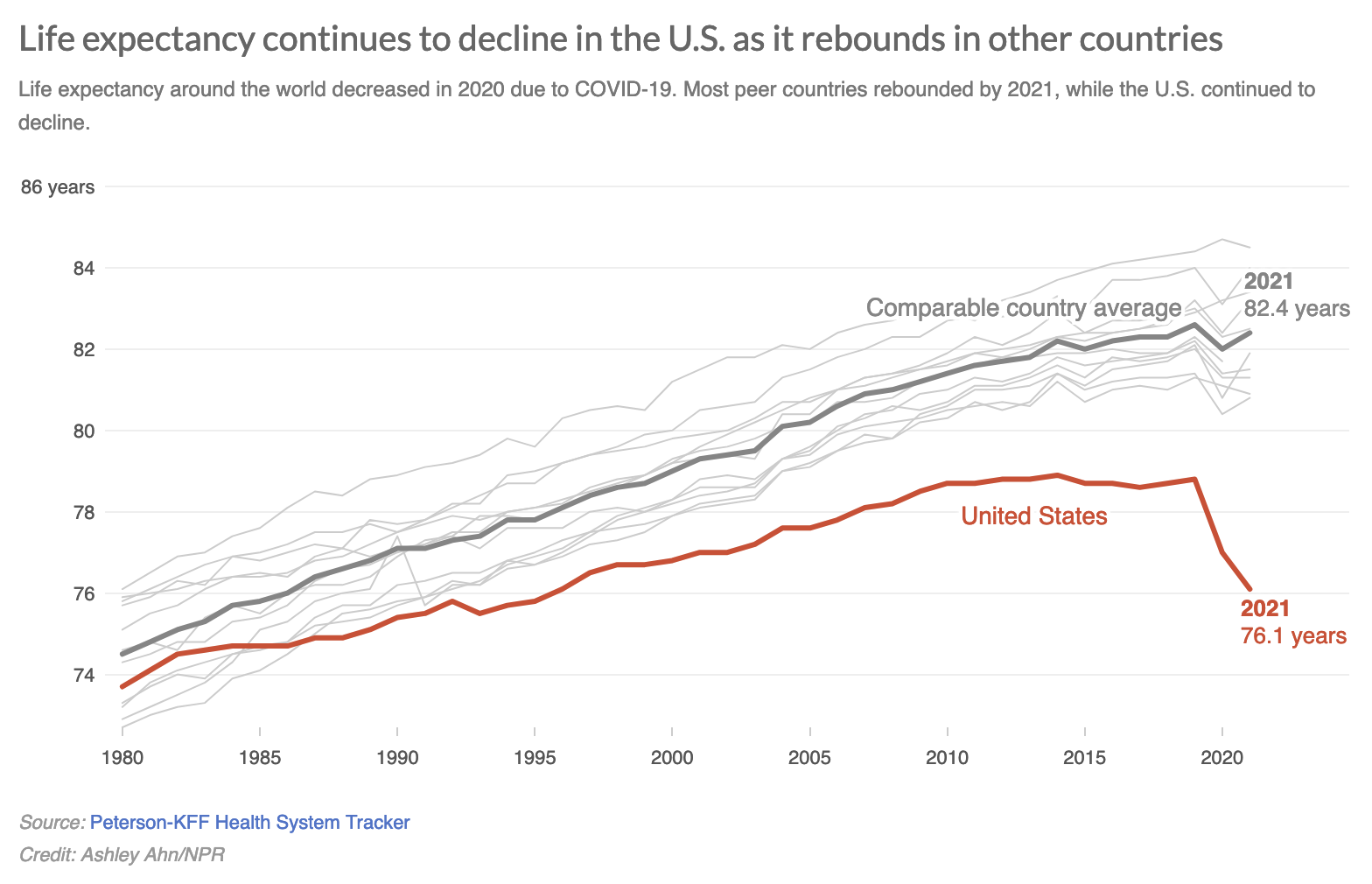

Life expectancy—the number of additional years a person can expect to live at a given age—dropped in the United States during the COVID years. It did the same in other wealthy nations. But in those nations, life expectancy has begun to climb again. In the US, it’s continued to plummet. That worsens a long-term trend.

The mortality gap has complex origins, but not so complex that they cannot be counteracted. Churches can and should be a part of the response.

The mortality gap can’t be fully explained by any of the factors we typically point to as causes. It’s not just COVID. It’s not opiates or school shootings, either. It’s not diabetes, strokes, heart problems or other preventable diseases. And it doesn’t stem only from inequalities. Even wealthy Americans fare worse than peers in other nations.

Instead, it’s kind of, well, everything. In 2013, researchers identified nine areas where Americans did worse than other countries:

- Infant mortality

- Injuries and homicides

- Teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases

- HIV/AIDS

- Drug-related mortality

- Obesity and diabetes

- Heart disease

- Chronic lung disease

- Disability

Understanding the mortality gap

Before we go any further, there are some important things to note here.

First, US health is not uniformly terrible—but it’s not great, either. According the study mentioned above, “The United States has higher survival after age 75 than do peer countries, and it has higher rates of cancer screening and survival, better control of blood pressure and cholesterol levels, lower stroke mortality, lower rates of current smoking, and higher average household income.”

Unfortunately, those advantages are outweighed by many other disadvantages. Experts suspect that even if the US equaled other developed nations on these factors, it would still lag them in average lifespan. For whatever reason, it’s less healthy to live here than in other parts of the world.

Second, these factors disproportionately affect younger individuals. About two-thirds of the mortality gap is due to the health problems of people under the age of 50. We expose young people to a lot of bad habits and risky situations—and we pay the price down the road.

Third, this applies to Wisconsin as well. The average life expectancy here has only risen by a little under two years since 1989. Almost every age bracket has seen a slight decline from their top values in that period. (In other words, we’ve slipped backwards a little.) Much of that stems from the increase in overdose deaths, which went up by 44% between 2009 and 2018.

It’s not easy to see what, if anything, connects all these factors. It could be the American health care system, individual behaviors, or social and economic inequalities. But none of these are very satisfactory answers. In the end, there’s a lot we don’t know about the situation.

What we do know is that all of this is happening in the background as the nation’s public health system is coming under tremendous pressure, both as a response to COVID measures and as part of greater ideological programs. That’s not a great situation in the here-and-now, of course. But it also leaves the US vulnerable to future health-related emergencies.

In short, the United States has made a lot of bad health decisions in the past forty years. A lot of bad health decisions. The consequences of those decisions are catching up with us in the same way a diet of hamburgers and unfiltered cigarettes will. Which is to say, a lot of people are dying before their time. A lot of people. To make matters worse, we’re poorly prepared for the next crisis, whatever that may be.

You didn’t need to sleep tonight, did you?

Churches can and should respond to this situation. That seems like the least representatives of the God who came to give humanity abundant life can do.

- Faith communities can respond directly to the factors mentioned above with health promotion, information sharing, companionship, advocacy and acceptance. We’re happy to help you get started.

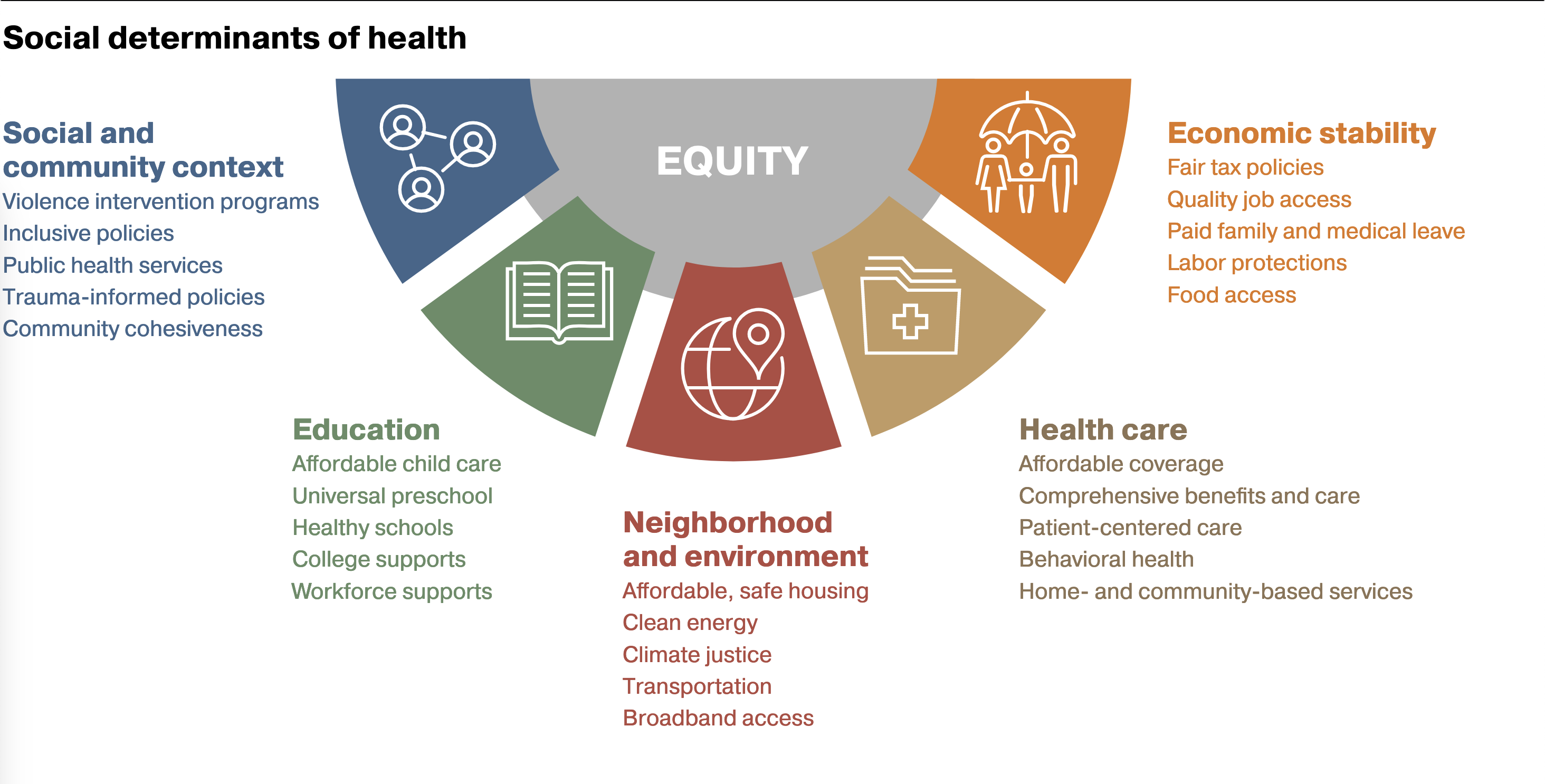

- Churches can also work on improving the social determinants of health. As Steven Woolf argues (and many studies support), one of the most important factors in determining future health is geography. Healthy people tend to live in healthy neighborhoods. The people in unhealthy neighborhoods face an uphill challenge.

- Raising awareness of the issues is helpful. Talking about the situation would make excellent fodder for an adult education class. So would a discussion of health inequities or social determinants. I’d love to lead a session, if you’ll have me (hint, hint).

- Advocacy is another powerful tool churches and other faith communities can use. The Community Health Program is not allowed to do any lobbying under the terms of its grants. But I can say that you know what’s fair and what’s not. If you need a place to start, check out the Wisconsin Public Health Association’s budget and policy priorities and see if you agree with them. And in a time where public health itself has become a political football, it’s important to make your voice heard on the subject.

Whatever you choose to do, it’s important to do something. It’s literally a matter of life—and increasingly—death.